African institutions are preparing for a digital future

Despite the current crypto crash, “it’s clear that institutions are preparing for a digital future,” says Richard Dennis, CEO of TemTum Group, a blockchain provider.

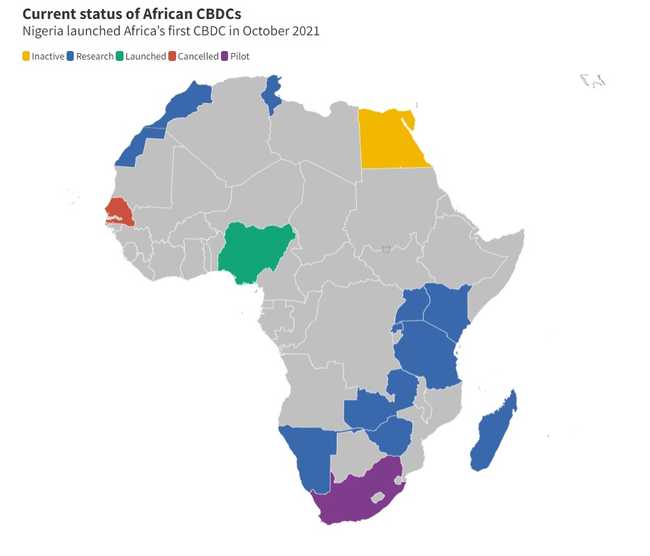

Countries across Africa are looking to use central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) to overcome infrastructural problems affecting the banking sector.

And far from being motivated by a desire to take advantage of cryptocurrencies as a “hyper-capitalistic technology” in the manner of millions of enthusiasts at the start of the decade, their object is to promote financial inclusion. By using the technology behind cryptocurrencies they aim to bring financial services to the hundreds of millions of Africans without bank accounts, facilitate domestic and cross-border payments and increase trade.

“The CBDC model will be very advantageous for Africa because it allows anybody to trade, it doesn’t need an internet connection, financial policies can be implemented much quicker, taxation and accountancy are simplified and, most importantly, in CBDCs there are no fees of transfer,” says Dennis, whose company advises central banks in Africa on how to implement the CBDC model.

What are CBDCs?

CBDCs are not cryptocurrencies. They are simply the digital representations of central bank money, and the government regulates them.

The value of a CBDC will rise or fall in relation to the dollar in the same way as the currency on which it is based, rather than fluctuating wildly like bitcoin.

However, CBDCs use the technical capabilities that arose from innovations in the crypto space to strengthen the central bank monetary system.

While based on the use of electronic wallets, CBDCs also differ from mobile money systems such as M-Pesa and Orange Money.

While the money used in the latter is based on ordinary cash and requires an intermediary to authorise payments, CBDCs can be used to make payments directly – for example, Nigeria’s eNaira allows peer-to-peer payments to anyone who has an eNaira wallet, without any charges.

Because the government controls the digital currency, situations such as the one that occurred with EcoCash in Zimbabwe cannot arise either.

“In the case of EcoCash in Zimbabwe, for example, the company had more money in the network than it had on bank accounts. At some point, it started printing its own money. EcoCash became the Zimbabwe dollar because everybody was using them,” explains Richard Dennis.

Will it be easy to implement CBDCs in Africa?

To implement CBDCs, Dennis says that it is “imperative” for central banks to work with existing private crypto and blockchain businesses, “who would use their expertise to implement such a network”.

In addition, Dennis argues that CBDCs do very little to the environment as they are not adding physical money to circulation or using the energy-intensive mining processes required by cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin.

“In Africa especially, you don’t want power as a form of security. So, what you end up with for CBDCs is consensus algorithms based on simple maths,” explains Dennis.

When asked about the main challenges of implementing CBDCs in Africa, Dennis does not see the lack of infrastructures in some countries as a barrier.

“The deployment of the technology is really easy, you can onboard 60m people within a month, it’s not a problem. The challenge is to get everybody to accept the generational change that is a digital currency,” he says.

Although Dennis agrees that it will be a long process, and very costly in time, he sees Africa as being increasingly tech-focused, especially the youth, which will make it easier to implement CBDCs.

Case study: One year of the eNaira in Nigeria

Last year, columnist Mushtak Parker wrote that, if carefully implemented, CBDCs could “produce large economic gains by increasing financial inclusion and reducing friction within the system”.

At the same time, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) launched the very first CBDC in Africa, the eNaira, following a ban on crypto transactions within the banking sector in the country.

The eNaira aimed to take advantage of the hype around cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin to provide people with a regulated digital currency, which would complement Nigeria’s physical currency and not be subject to the volatility of the crypto market.

As cryptocurrencies were gaining popular support in Nigeria, especially from the youth, the eNaira was released almost in a hurry to counter the popular demand for bitcoin, which was seen as financing terrorism and encouraging tax evasion.

However, after almost a year in use, the eNaira app has been downloaded only by 80 merchants across Nigeria and, out of the 700,040 individual downloads, only 14,000 people are now funding their eNaira wallets.

If technical issues at the release of the eNaira app have not helped in promoting the CBN’s initiative, Frank Eleanya, head of the tech news desk at BusinessDay in Nigeria, identifies a few other important factors.

“The banks and fintech companies in Nigeria were already providing all the services that eNaira was intended to provide,” says Eleanya.

“If you then tell the banks to go ahead and push this product, what happens to the products they already have on the market and spent millions on?”

The very essence of the CBDC project, namely a regulated digital currency controlled by the CBN, has been called into question by banks in Nigeria.

“The blockchain that controls the eNaira was going to be controlled by the Central Bank, meaning that banks would not be able to lay their services on the technology,” says Eleanya.

“But banks have shareholders that they need to answer to, and the eNaira does not guarantee them any incentives, so they slowly abandoned it,” says Eleanya.

As far as the users are concerned, the promise of “banking the unbanked” has not yet been realised in the Giant of Africa, where 36% of the adults remain completely financially excluded.

However, if financial inclusivity has not improved under eNaira, this has to do more with the current regulation of mobile money in Nigeria than the effectiveness of CBDCs.

“In Nigeria, when it comes to mobile money, the mobile number used has to be resident in a bank. If it is not the case, you are not allowed to have financial services in the country. That is the barrier that we have,” says Eleanya.

Thus, the promise of financial inclusion has failed to materialise for the 40m Nigerians currently without a bank account, whether they possess a mobile phone or not.

Lessons from the eNaira

What happens in Nigeria should not make the case for future CBDC implementation in Africa but help us understand the limits of the system.

One lesson to draw from the Nigerian case study is that future CBDCs in Africa cannot be implemented without talks between central banks and mobile money providers.

“There are trust issues in Nigeria. People cannot trust the CBN to be an operator. That does not even make sense: you cannot compete with the market you are trying to regulate,” says Eleanya.

“The regulation has to change so that the telcos can go to the rural areas and open bank accounts for the people.”

Trust issues might also appear in other parts of Africa when other governments start to create their own CBDCs.

With bitcoin, governments have feared the instability of the market. With CBDCs, as far as Nigeria is concerned, people have feared the poor management of the government.

As a result, a blended solution involving telcos that have a significant footprint in the local financial market and Central Banks might pave the way for successful digital currencies in Africa.